Everything You Need to Know You Learned in Kindergarten!

How can undergraduate education be improved? In 1987, Arthur W. Chickering and Zelda F. Gamson answered this question when they wrote “Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education.” They defined what good education means at the undergraduate level. The seven principles are based upon research on good teaching and learning in the college setting.

These principles have been intended as a guideline for faculty members, students, and administrators to follow to improve teaching and learning. Research for over 50 years on practical experience of students and teachers supports these principles. When all principles are practiced, there are six other forces in education that surface: activity, expectations, cooperation, interaction, diversity, and responsibility. Good practices work for professional programs as well as the liberal arts. They also work for a variety of students: Hispanic, Asian, young, old, rich, poor.

Teachers and students have the most responsibility for improving undergraduate education. However, improvements will need to be made by college and university leaders, and state and federal officials. It is a joint venture among all that is possible. When this does occur, faculty and administrators think of themselves as educators that have a a shared goal. Resources become available for students, faculty, and administrators to work together.

The goal of the seven principles is to prepare the student to deal with the real world.

Building rapport with students is very important. The contact between students and teachers are vital to the students’ success. One of the main reasons students leave school is the feeling of isolation that they experience. The concern shown will help students get through difficult times and keep working. Faculty have many avenues to follow to open up the lines of communication.

Technology, like e-mail, computer conferencing, and the World Wide Web/Internet, now gives more opportunities for students and faculty to converse. It is efficient, convenient, and protected. It allows more privacy so that students are able to discuss more openly without fear that other students are going to hear. E-mail also gives student more time to think about what they want to say. With these new alternatives to face-to-face communication, interaction from more students should increase within the classroom.

When students are encouraged to work as a team, more learning takes place. Characteristics of good learning are collaborative and social, not competitive and isolated. Working together improves thinking and understanding.

Cooperative learning has several benefits. Students care more about their learning because of the interdependent nature of the process. Retention is higher because there is a social and intellectual aspect on the content material. Students also find the method more enjoyable because there is no competition placed upon them. Cooperation, not competition, is more effective in promoting student learning.

Learning is an active process. Students are not able to learn much by only sitting in classes listening to teachers, memorizing pre-packaged assignments, and churning out answers. They must be able to talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, and apply it to their daily lives. Students need to make learning a part of themselves.

Promoting active learning in higher education is a struggle because of the learning background that many students come to classes with. This is due to the fact that the norm in our nation’s secondary schools has been to promote passive learning. A large amount of information needs to be covered with not enough time, so teachers resort to lecture in order to economize their time to cover as much material as possible. Students progress from topic to topic with no real understanding of the content and how it relates to their life. Effective learning is active learning. The concept of active learning has been applied to curriculum design, internship programs, community service, laboratory science instruction, musical and speech performance, seminar classes, undergraduate research, peer teaching, and computer-assisted learning. The common thread between all these events is to stimulate students to think about how they as well as what they are learning and to take more responsibility for their own education.

By knowing what you know and do not know gives a focus to learning. In order for students to benefit from courses, they need appropriate feedback on their performance. When starting out, students need help in evaluating their current knowledge and capabilities. Within the classroom, students need frequent opportunities to perform and receive suggestions for improvement. Throughout their time in college and especially at the end of their college career, students need chances to reflect on what they have learned, what they still need to know, and how to assess themselves.

The importance of feedback is so obvious that it is often taken for granted during the teaching and learning process. It is a simple yet powerful tool to aid in the learning process. Feedback is any means to inform a learner of their accomplishments and areas needing improvement. There are several different forms that feedback can take. They are oral, written, computer displayed, and from any of the interactions that occur in group learning. What is important is that the learner is informed and can associate the feedback with a specific response.

Learning needs time and energy. Efficient time-management skills are critical for students. By allowing realistic amounts of time, effective learning for students and effective teaching for faculty are able to occur. The way the institution defines time expectations for students, faculty, administrators, and other staff, can create the basis for high performance from everyone.

An easy assumption to make would be that students would be more successful if they spent more time studying. It makes sense but it over simplifies the principle of time on task. Student achievement is not simply a matter of the amount of time spent working on a task. Even though learning and development require time, it is an error to disregard how much time is available and how well the time is spent. Time on task is more complicated than one might assume.

Expect more and you will get it. The poorly prepared, those unwilling to exert themselves, and the bright and motivated all need high expectations. Expecting students to perform well becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy when teachers and institutions hold high standards and make extra efforts.

Although it is often only discussed at the instructional level, high expectations also includes the students’ performance and behavior inside and outside the classroom. College and universities expect students to meet their high expectations for performance in the classroom, but also expect a personal and professional commitment to values and ethics. They include the discipline to set goals and stick with them, an awareness and appreciation of the diversity of society, and a philosophy of service to others.

There are many different ways to learn and no two people learn the same way. Students bring different talents and learning styles to the classroom. Students that excel in the seminar room may be all thumbs in the lab or art studio and vice versa. Students need the opportunity to show their talents and learn in ways that work for them. Then, they can be guided into new ways of learning that are not as easy for them.

The meaning of diversity is very clear from effective institutions. They embrace diversity and systematically foster it. This respect for diversity should play a central part in university decisions, be apparent in the services and resources available to students and resources available to students, be a feature of every academic program, and practiced in every classroom.

433 Library | Dept 4354 | 615 McCallie Ave | Chattanooga, TN 37403 | p (423)425-4188 | Email Us!

Posted: May 2, 2019 8:50 am

If you love your children and want to help them grow into stable, thoughtful, productive, loving adults, here are 10 things you should avoid doing.

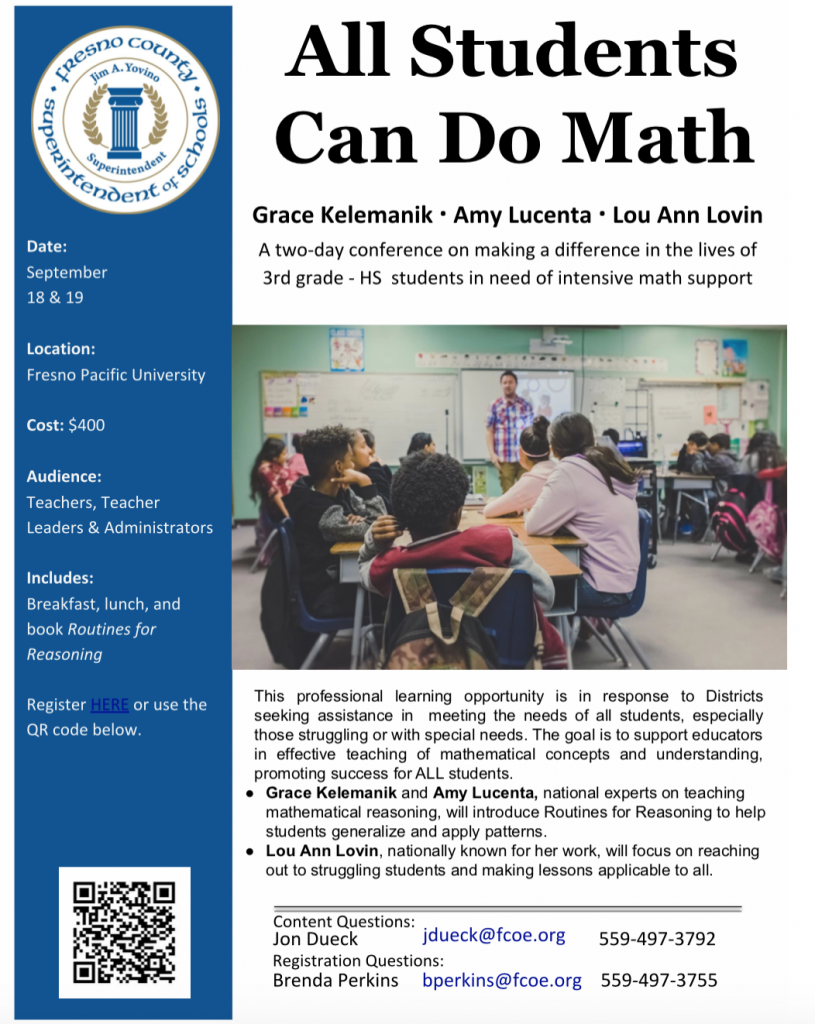

Their brain controls everything they do—how they think, how they behave, how they relate to others. When their brain works right, they work right. When they have trouble in their brain, they have trouble in their life. And if they have trouble in their life, you have trouble in your life. Leading edge brain imaging technology called SPECT shows the health of the brain. In the images below, you can see a healthy brain, a brain damaged by trauma (such as falling off a bike), and the brain of someone with ADD/ADHD. Seeing is believing. If you want your child to be their best, you have to take care of their brain and teach them how to do so.

Healthy SPECT Brain Scan: full, symmetrical activity

Head Trauma: damage to right frontal lobe

Classic ADD/ADHD: low activity in prefrontal cortex

Relationships require special time. The most effective exercise you can do is spend 20 minutes of quality time a day with your child—listening and doing something they want to do (within reason).

When your kids are trying to talk to you, don’t speak over them. Learn to be an active listener. Let them say their piece and then repeat back what you heard so they know you have heard them.

Don’t tell your child, “You’re a spoiled brat.” This is not helpful, and they will internalize these negative names and begin to believe them.

Letting your child do whatever they want may make them “happy” in the moment, but it can be detrimental in the long run. Children need clear boundaries. Kids who have the most psychological problems usually have parents who didn’t set boundaries for them. Be firm and be kind.

The human brain’s frontal lobes—which are involved in planning, judgment, and impulse control—are not fully developed until about age 25. You need to be your children’s frontal lobes until theirs develop. This means checking in on what your kids are doing and with whom they are doing it. This doesn’t mean being a helicopter parent, it means you care.

If you’re a poor role model, your kids will pick up on that and follow your lead. If you say, “eat your vegetables” but you constantly snack on candy or potato chips, they will likely opt for the foods they see you eating.

Try to notice when your kids do things you like—cleaning up their room, finishing their homework, or brushing their teeth.

On average, it takes 11 years from the time kids develop symptoms of a mental health condition to first evaluation. This is just wrong. Struggling with symptoms of ADD/ADHD or anxiety and depression can negatively impact their ability to succeed in school, in their friendships, and in life.

If you are suffering from a mental health condition—whether it’s PTSD, bipolar disorder, or something else—it can devastate your children. Remember the saying, “Put your own oxygen mask on first.” You need to take care of yourself and be the best version of yourself to be the best parent.

At Amen Clinics, we have helped thousands of parents and children enhance their brain health and improve their performance at work, at school, and in relationships. If you or your child are struggling with a mental health issue or consequences of head trauma, schedule a visit or call 855-972-4857.

We teach and lead because God has called us to do so. For thousands of years God has asked people to participate in the work of helping others come to know God and live as people of faith. These teachers and leaders have come in many shapes and forms, from many backgrounds, and with many levels of ability. But each has somehow heard a call to teach and has responded.

You may not even realize that you responded to a call. You may think you merely answered a plea for help, or just knew it was your turn to help the third graders! But God’s call can come in many ways:

Take a brief inventory before exploring Basics of Teaching.

Read each statement; then circle the number that best describes your situation.

1 = Not at all; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Mostly; 4 = Definitely

1 2 3 4 I understand that my teaching is in response to a call from God.

1 2 3 4 I know I never enter a classroom alone, for God is always present with me.

1 2 3 4 I understand that one of my primary roles as a teacher is to model the Christian faith to the best of my ability.

1 2 3 4 I believe the role of a teacher is not only to share information but also to create an environment where God can transform us into the people God wants us to be.

1 2 3 4 I understand how the primary task of the local congregation relates to my role as a teacher.

1 2 3 4 I know that people prefer different learning styles, and I am able to incorporate these different styles into my lesson plans.

1 2 3 4 I use a wide variety of methods in my teaching, and I am able to adapt them to the preferences of my class.

Why We Teach

Students, Participants, and Partners in Teaching

The Role of a Teacher

The Primary Task of Every Congregation

Many Ways to Teach

Using Curriculum Resources

WHY WE TEACH

You are called. Read the story of Moses’ call to leadership in Exodus 3:1–4:17. Notice some of Moses’ feelings and concerns that you also experienced when first asked to teach or lead. God’s call to you may not be as flashy as Moses’ call through a burning bush, but God’s need of you and God’s promise of support are just as strong as they were in biblical times.

Like Moses, your first reaction to a call may have been reluctance or fear. That’s normal. When God gives us a task, it can seem overwhelming and we may feel ill-equipped. Moses tried to argue with God and pointed out all of his own personal shortcomings. God assured Moses that his gifts were sufficient and that help would arrive when needed. Like Moses, we can be assured that God will use whatever skills we have and that we will find the help we need to be an effective teacher or leader.

God’s Presence

God does not call us and then leave us alone. As a teacher and spiritual leader, you have the promise that God will be with you. Story after story in the Bible tells us that God wants to be in relationship with us and to be present for us at all times. For example, “I will be with you,” God says to Moses in Exodus 3:12, and promises to help. When God sends Aaron to assist Moses, God adds, “I will . . . teach you what you shall do” (Exodus 4:15).

Jesus promised his followers that the Holy Spirit would be with them: “. . . I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate, to be with you forever” (John 14:14-16). You can trust that God’s Spirit is present with you in the classroom, enabling you to accomplish things you could not do on your own.

A wise teacher once told a group of people who were learning how to teach that “God goes before me into every classroom I enter. God is present in that room before, during, and after I teach. I don’t have to do it all.” God is already present and working in the lives of the people you lead. God will continue to work within them long after you are no longer around. Thanks be to God!

God’s presence also assumes God’s grace. In church we often hear, sing, and read about the concept of grace. Very simply, grace means God’s loving concern for every person. There is nothing we can do to earn it; God simply loves us. There is no certain number of good deeds we must perform to qualify for it; we just receive it. Grace is the overwhelming, undeserved blessing of God’s love. It is this grace that surrounds us, supports us, and helps us lead and teach. You are not responsible for changing the lives of your students by your teaching; it is the God of grace who does this. You just tell the story of God’s love, and trust God to do the rest.

As a teacher you may encounter the term means of grace. This refers to an action or practice that is a channel for God’s grace. Means of grace are things we do that bring us into contact with God and open the possibility for us to grow closer to God. John Wesley, the founder of the Methodist movement, felt that each Christian (especially leaders) should be involved in these practices. The means of grace include (but are not limited to)

As teachers and leaders we should be thinking about how we are personally involved in these means of grace and how we can help our students learn to practice them. The very act of teaching can be a means of grace. As we teach and as we open ourselves to learn, God’s mysterious work of grace happens; and all of us—teachers and learners alike—are transformed.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1.Reread and reflect on the Scriptures mentioned above. Use them in a devotional setting–let the words seep into your heart; look for the word of God to you. What do these stories and promises hold for you? Do you have experience of God in ways suggested by those passages? How is God calling you?

2.Look through The United Methodist Hymnal (or other hymnal used by your congregation). List the hymns that include the word grace. How is the word used? How do these hymns help you better understand the meaning of God’s grace?

For Further Study and Reflection

1.Gather with other teachers and small group leaders to share your stories and questions about how God has called you. What do you think God wants of each of you? What gifts do you see in yourself? Call forth and name the gifts and strengths you see in each other. Are any of those gifts complementary? How might you work together in different ways to enhance the teaching ministry?

2.Commit with other teachers to form a covenant group (for several weeks, at least) to study and consider prayerfully Three Simple Rules: A Wesleyan Way of Living, by Rueben P. Job (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007; available through Cokesbury). The third section specifically addresses the means of grace, but don’t skip the prior sections.

STUDENTS, PARTICIPANTS, AND PARTNERS IN TEACHING

No one comes to a class or small group completely “on empty.” The designated teacher not only has learners, but persons with something to offer as well.

A Cloud of Witnesses

Some of our best teachers are not immediately present. Who are some of the people who have been witnesses to the Christian faith? Who modeled or taught you what it means to be a follower of Christ? Thank God for their witness!

Hebrews 12 begins with the words, “Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses . . .” This phrase follows a long listing of biblical people who were examples of faith. People like Abraham, Sarah, Moses, Esther, David, Mary, Paul, and many others not called by name— these people have gone before us and sought to be faithful to God. You can add other names to this list: people who are important in the history of your local congregation, pastors who guided you, parents who taught you the faith, Sunday school teachers who helped you grow. You are “surrounded” by these people when you seek to lead a group or teach a lesson. You can almost imagine them sitting in a balcony of your classroom cheering you on!

Class Members

Whether you teach three-year-old children or older adults, whether your group has two members or two hundred, you can know that the Holy Spirit is present. Jesus said, “For where two or three are gathered in my name, I am there among them” (Matthew 18:20). A teacher learns quickly that students and group members quite often “teach” the teacher. Group members come with a wealth of experience, knowledge, and backgrounds that one leader cannot provide. Often a student will share an insight that the leader has never thought about. Even the youngest learners can teach by the questions they ask and the different perspectives they bring to the subject at hand. A young child’s spontaneous hug and “I love you” can teach the teacher something about God’s grace. Teaching is a mutual process where all share together in the experience of teaching and learning. The older the student or group member, the more they bring and the more they expect to be allowed to bring.

The Congregation

You have been asked to teach on behalf of your congregation. Hopefully the congregation is supporting you by providing the space, study materials, and supplies you need to be effective. Other ways congregations can support teachers include

If you would like to be supported in any of these ways, ask! Sometimes congregations just haven’t thought of all the possibilities.

The United Methodist Connection

United Methodist congregations are connected to one another in a special way. Local churches are joined together into districts; districts are joined into annual conferences; annual conferences are joined into jurisdictions; and jurisdictions are joined together with conferences outside the United States to make up the entire United Methodist denomination. The general agencies help support all of these different parts. Just as local congregations share their resources of money and service with these larger bodies, so the districts, conferences, and general agencies share their knowledge, resources, and skills with local congregations. Ask your pastor or Sunday school superintendent about training events and resources that might be available in your area. A district or conference staff person may be available to help provide training for teachers and leaders in your church. Perhaps several congregations located near one another could sponsor a joint learning event. General agencies provide written and internet-based resources that can be helpful.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Think more deeply about your own “cloud of witnesses.” What was it that made them good models and teachers? good spiritual mentors and leaders? Dig more deeply than, “She cared about me” to what it was that she did to demonstrate care or further than “the lessons were good” to what sort of preparation made them good. By delving more specifically into your reflections you can identify the success factors that you may be able to adopt and adapt. What have you learned that you can make your own?

2. Consider also the members of your class or group. What does each of them bring to the session? How might their knowledge and experience augment your own? What contributions have you missed so far that could add value to the rest of the group?

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Invite members of the congregation who are not currently in a class or group to meet together to share what inspiration, experience, gifts, strengths, or ideas they might contribute, on occasion, to the education ministry. Observers and past participants may have a perspective and gifts that need to be considered. Friends of the education ministry may be willing to be partners in some fashion, even if they are not present in a group each time it meets.

2. Call your conference office or go online to the conference web page to see what sort of helps are available.

THE ROLE OF A TEACHER

You have probably known someone in your life who was a truly gifted teacher. He or she seemed to have a deep knowledge of a subject, effortlessly knew what method to use, and was able to inspire others to learn. In fact, teaching is identified in the New Testament as one of the spiritual gifts given to people to be used in God’s service.

Many of us may never claim the title of gifted teacher, but all of us fill a teaching role at some point. Anytime we encourage, share information, guide, support, challenge, parent, or tell another about how God has acted in our lives, we are filling a teaching role. One resource states it this way:

In a real sense, every person in the congregation participates in the teaching ministry. We teach through worship, through service, through engagement in the administrative tasks of the church. Everyone in the congregation is both teacher and learner. (From Foundations: Shaping the Ministry of Christian Education in Your Congregation; copyright © 1993 Discipleship Resources; used by permission; page 4.)

One of the characteristics of a good teacher is being a good learner and a good listener. Teachers model for their students the value of learning. We can never learn all there is to know about teaching, nor will we ever have all the answers. Trust, value, and seek the wisdom of your class or group members. Listen to the questions and reflections of their hearts, knowledge, and experience.

Who do you consider the best teacher you ever experienced? What did he or she do that was so memorable or effective? It may be helpful to think of the following three words to describe your role as a teacher:

Model

A teacher is one who models the Christian faith, hopefully to the best of his or her ability. People learn by watching others’ actions and words. What we do is more powerful than what we say; how we live is stronger than how we claim we should live. Your students (of all ages) will watch you and learn from you. It is vital, then, that you model and teach well. The most powerful Christian teacher is one who not only recites, “Do to others as you would have them do to you” (Luke 6:31), but also actually practices it. An effective teacher is one whose faith is evidenced in his or her actions in the congregation and the community.

This does not mean that you cannot accept a teaching role until you are a perfect Christian. (If it did, our teaching ministry would have ended with Jesus!) It does mean that you understand the importance of seeking to grow into the likeness of Christ. A teacher should be growing in his or her own knowledge of the Bible, learning to pray, attending worship, and setting the example of a follower of Christ.

Formation

The role of a teacher of the faith is not just to pass on information or facts. It is to help people be formed as disciples (learners and followers) of Christ, and transformed into the people God has created them to be. Romans 12:2 says:

Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God— what is good and acceptable and perfect.

Transformation is the process of being converted or changed so that our fullest humanity can be realized. Sometimes transformation is a slow process, like water rushing over rocks for years and slowly changing their shapes. Other times it seems to happen much more quickly, like a river flooding over its banks and radically altering the shape of the land. In either instance, transformation is the work of God in our lives that changes us more and more from our current state of being into the people God wants us to be.

The good news for teachers is that we are not responsible for this transformation—God is! A teacher’s role is only to create places, times, and atmosphere where people can learn about God, hear the stories of Christian people, experience Christian community, and talk about how God may want them to live in their everyday world. We trust God to do the rest.

Information

Part of the teaching responsibility is, indeed, to share information. There is more to learn about the Christian faith than any of us can ever know: information about the Bible and the stories in the Bible, the history of the church, theology (or how people think and talk about God), facts about the beliefs and practices of The United Methodist Church, and much more.

Much of the information you will share will come from printed study resources provided by your congregation. Other information will come from your own personal study and reflection. Your class or group members will also bring their collective and individual wisdom. No teacher will ever know all the answers. Yet we can help people learn some important information that will help them know what it means to be a Christian and will assist them in their walk with God.

Building Relationships

Perhaps one of the most important things a teacher can do is build relationships. A teacher first works to strengthen his or her relationship with God. Daily prayer and reflection, study of Scripture, participation in worship, involvement in service activities—these are just a few of the practices that can draw each of us closer to God. Next, a teacher seeks to develop a strong relationship with the students or group members in the class. Few Christians remember much of what a Sunday school teacher actually taught them. What they remember most is the warm and caring relationship with the teacher—or the lack thereof! A good teacher also pays attention to the relationships between members of the group, helping them build an open, supportive Christian community.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Consider how your class time is spent in information-giving.

2. Think next about how your class or group is structured to allow for formation and transformation.

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Gather the other teachers and group leaders together to explore the reference materials that each of you has. What is in your church library or pastor’s study that might be available to you? Do you search out information in sources other than the printed curriculum or study Bible notes? Commit to more background study as part of your preparation for a month or so to see what difference it makes in your teaching.

2. Work with the other teachers, especially those who work with the same approximate age-level, to discuss how they structure the class for transformation. What can you learn from and teach to the others? If you are unsure about how to structure your time to allow for transformation, consider joining with several other people for your own devotional time together (not primarily study time). Use candles or icons for focus; take time to pray silently and together; search the Scriptures for the service challenges they offer you and embrace something. Go back to the group to reflect on your own experiences and to explore how to set a similar stage in your learning setting.

THE PRIMARY TASK OF EVERY CONGREGATION

The primary task of every congregation is

The primary task as described here is not four things, but one task with several dimensions. That one task can also be described as disciple making. The commission to be God’s partner in making disciples is the responsibility of every congregation. All the ministries, including the ministry of education and Christian formation, should align around what it means for your congregation to make disciples in its own time and context. Each ministry area, class, and group has a stake in disciple making. It may be someone else’s “job,” but it surely is your job.

Some groups will do one dimension more completely than others, and so the complementarity of all the groups and classes is important. Together, they engage in the primary task– all dimensions of it.

As a teacher or leader of a small group, you can pay attention to this primary task by

Each week you help your students reflect on how they live out their faith in the community. Then you send them out to begin the process again.

This may sound complicated, but it can be as simple as calling a child by name as he or she enters the room and giving the child a hug, telling your students stories about God and Jesus Christ, talking with your students about how a Christian tries to follow Jesus, then praying as you send your students out that each child, youth, and adult can find a way to help others in the name of Jesus.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Think about this primary task by rewriting it in your own words or by drawing an image or diagram of it. What examples do you see of each dimension in the church, over all?

2. List the things that you do in your class that relate to each part of the primary task. If you are not addressing each dimension, what’s missing? What can you do to engage that dimension?

For Further Study and Reflection

Gather with a group of other teachers or education leaders and study the portions of The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church (or the “marching orders” of your faith tradition) to gain further insight into the church’s mission and goals. How can you incorporate these understandings in your class or group and in the way you approach teaching?

MANY WAYS TO TEACH

There are many different methods and activities to use in teaching and leading groups. There are entire books dedicated to explaining different ways to teach and learn. Most study resources designed for church classrooms suggest a number of different methods. Just remember that the most important person in deciding which method to use is not the teacher but the learner.

Ways People Learn

Listed below are a number of ways that individuals learn.

The Needs of the Learner

An effective teacher has a deep knowledge about the students he or she teaches. Only after reflecting on the answers to the following questions should a teacher decide which methods to use.

Choose a variety of different methods so that over several weeks you can meet the needs of all of your group members. Don’t be afraid to try new methods and approaches—you may find your students more responsive than you think. (See also the teaching methods in Using Curriculum Resources.)

When you have carefully considered the answers to these questions and thought about your students’ needs and preferred ways of learning, you will be much better prepared to choose methods and activities that will make the class come alive. Remember—you teach people, not lessons!

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

1. Take the time to jot down answers to the three questions above. What insights have emerged from a thoughtful consideration of these questions that helps you understand your group members better?

2. There are numerous inventories related to multiple intelligences (the ways people learn). Search the internet for “multiple intelligences” to find an inventory and complete it yourself. If your group members are old enough to understand and complete an inventory, print it and ask them to complete it. (To avoid copyright violation, record the results and discard the inventories. Do not share them beyond the class.) Use this information to evaluate your teaching methods.

For Further Study and Reflection

Go back to the list of ways people learn and place each class or group member’s name by the way that seems strongest for them; then record the lowest scores in the same way. (Remember that there is no right or wrong to this; it just is.) Next look back over your past few lessons. If you adapted or eliminated activities, in what category did they fall? Did you favor your own strongest learning style(s)? In future planning/ adapting, try to offer a blend of several methodologies, then ask your group members to evaluate the session.

USING CURRICULUM RESOURCES

Most study materials provide a number of different options for teaching and learning activities. You will want to pick and choose among these options in light of the preferences of your class and your own level of comfort and interest. But the resource materials are only the beginning point for your lesson plan. You must make the lesson plan your own.

Some teachers like to teach from the book or leader’s guide. Others prefer to write out their plan or outline on a separate piece of paper. It doesn’t really matter how you go about it. The important thing is for you to know the material well enough to focus more on what is happening in the room than on your notes.

Be flexible! You never know what might happen when we gather to learn in God’s presence. If the Spirit is moving in the room and people begin to share in a deep manner, let it happen. Don’t rush on to another activity because you planned it that way. On the other hand, if the method you thought people would enjoy and would take thirty minutes to complete turns out not to work at all and is over in ten minutes, move on to the next thing you have planned. Plan an extra activity or two that you can add if you need.

Variety of Methods

Here is a list of possible learning activities, methods, and aids.

What a wonderful list of creative options! The problem is rarely, “What will I do?” but instead, “Which one of my options is better?” Remember, any of these methods can be effective if they are appropriate for the age level and needs of your group members and they are chosen because they will help people connect the good news of God’s love to their own particular life situations.

Dig Deeper: Personal Exercises

Look again at the list of methods and check any activity that you have used in the past. Using a different mark, check any method you want to know more about or might consider using in the future.

For Further Study and Reflection

1. Ask to have aDisciple orChristian Believer group (www.cokesbury.com) orCompanions in Christgroup in your church particularly for teachers and small group leaders who desire to deepen their own knowledge and faith life.

2. Start a study group for teachers and small group leaders using one or more of these teacher development resources, fromThe Upper Room bookstore,unless otherwise noted.

Expectations…say them, repeat them and start the year with them. Be consistent and follow through. — Audrey Fisher

Discipline – something they don’t teach enough about in teacher preparation classes. Figuring out how you are going to handle discipline in your classroom ahead of time will put you ahead of the game. Rules are just like other instructional activities. They have to be taught, reviewed, and reinforced. Being consistent, learning from your mistakes and developing a rapport with your students is a longstanding goal of all teachers. There are a number of ways in which a teacher can promote good discipline in the classroom.

Want additional strategies and tips for effective classroom management?

Check out the online class offered through the WEA Professional Development Academy. Credit is available for the class. Information and sign-up directions are given at https://pdalearning.org.

Mentors – An Initial Educator’s Best Friend: There is help available if you or your district is in need of high quality, flexible mentor training that coincides with Wisconsin Educator Standards. For more information, contact Debra Berndt, Director of the WEA Professional Development Academy at berndtd@weac.org or check out the information provided at weac.org under the WEA Professional Development Academy.

Managing Your Time

Time can’t be saved; it is only spent. Although you can’t get any more hours from a day, you can develop habits that will make you more productive.

You may have already discovered that your teaching duties demand a great deal of time. You may feel that there’s no time left to manage after you schedule all your classes and assigned activities. Gaining control begins by discovering how you currently spend your time.

Determine which tasks must be accomplished early in the day when you have the most energy so you can avoid that frantic feeling throughout the day.

Procrastination is your number one enemy. Procrastination means performing low-priority activities rather than high-priority activities. It can result in more work, more pressure, the loss of self-esteem, and health problems.

Here are some coping strategies for each of the major reasons people procrastinate:

Dealing with an unpleasant task

Dealing with difficult or overwhelming tasks

Dealing with indecision (fear of failure)

Learn to say NO

California Math Project aka CPM is the best curriculum for mathematics. I have viewed many textbooks as a Mathematics Consultant and many borrow from the idea of this program but not able to create anything near as great. This project began in 1982 and is written by teachers for teachers. Students learn WHY they learn the mathematics and how it pertains to life. It’s answers the age old question of when am I ever going to use this. If students don’t see the point of learning the math, they only memorize to pass a test.

I hear pros and cons to this project. I was an avid user of this curriculum and know how and why it works. Teachers that choose not to use it are either weak in their own math skills or aren’t properly trained to use the program. This is what is best for students and teachers need to

You cannot pick and choose what to use in the pages, you must follow the order of how it is written for it to work.

I would love to see mathematics taught across the country in this fashion. I was blessed to have had the opportunity to utilize it and know that my students were better off for having the opportunity to learn this way.

It’s alarming but true: studies have shown that 35% of teachers leave the profession during the first year. By the end of the fifth year, 50% of teachers have left the field! — From Teachers Helping Teachers, Springfield Public Schools, Springfield, MA

The first year of teaching is a difficult challenge. If you are currently in your first year of teaching, the graph above probably applies to you. And you are most certainly not alone! Whether you are currently feeling extremely overwhelmed or abundantly triumphant, other first-year teachers are going through the same thing. The University of California Santa Cruz New Teacher Project has worked to support the efforts of new teachers. They have identified phases through which all new teachers progress. The phases are very useful for mentors and new teachers as they work together the first year. Teachers move through the phases from anticipation, to survival, to disillusionment, to rejuvenation, to reflection, and then back to anticipation.

Anticipation Phase

The anticipation stage begins during the student teaching portion of preservice preparation. The closer student teachers get to completing their assignment, the more excited and anxious they become about their first teaching positions. They tend to romanticize the role of the teachers and the positions. New teachers enter with a tremendous commitment to making a difference and a somewhat idealistic view of how to accomplish their goals. This feeling of excitement carries new teachers through the first few weeks of school.

Survival Phase

The first month of school is very overwhelming for new teachers. They are learning a lot at a very rapid pace. Beginning teachers are instantly bombarded with a variety of problems and situations they had not anticipated. Despite teacher preparation programs, new teachers are caught off guard by the realities of teaching.

During the survival phase, most new teachers struggle to keep their heads above water. They become very focused and consumed with the day-to-day routine of teaching. There is little time to stop and reflect on their experiences. It is not uncommon for new teachers to spend up to seventy hours a week on schoolwork.

Particularly overwhelming is the constant need to develop curriculum. Veteran teachers routinely reuse excellent lessons and units from the past. New teachers, still uncertain of what will really work, must develop their lessons for the first time. Even depending on unfamiliar prepared curriculum such as textbooks, is enormously time consuming.

Disillusionment Phase

After six to eight weeks of nonstop work and stress, new teachers enter the disillusionment phase. The intensity and length of the phase varies among new teachers. The extensive time commitment, the realization that things are probably not going as smoothly as they want, and low morale contribute to this period of disenchantment. New teachers begin questioning both their commitment and their competence. Many new teachers get sick during this phase.

|

Top 5 Concerns of New Teachers 1. Classroom arrangement and management 2. Curriculum planning 3. Establishing a grading system that’s fair 4. Parent conferences 5. Personal sanity |

Compounding an already difficult situation is the fact that new teachers are confronted with several new events during this time frame. They are faced with back-to-school night, parent conferences, and their first formal evaluation by the site administrator. Each of these important milestones places an already vulnerable individual in a very stressful situation.

During the disillusionment phase, classroom management is a major source of distress. New teachers want to focus more time on curriculum and less on classroom management and discipline.

At this point, the accumulated stress of the first year teachers, coupled with months of excessive time allotted to teaching, often bring complaints from family and friends. This is a very difficult and challenging phase for new entrants into the profession. They express self-doubt, have lower self-esteem, and question their profession commitment. In fact, getting through this phase may be the toughest challenge new teachers face.

Rejuvenation Phase

The rejuvenation phase is characterized by a slow rise in the new teacher’s attitude toward teaching. It generally begins in January. Having a winter break makes a tremendous difference for new teachers. It allows them to resume a more normal lifestyle, with plenty of rest, food, exercise, and time for family and friends. This vacation is the first opportunity that new teachers have for organizing materials and planning curriculum. It is a time for them to sort through materials that have accumulated and prepare new ones. This breath of fresh air gives novice teachers a broader perspective with renewed hope.

They seem ready to put past problems behind them. A better understanding of the system, an acceptance of the realities of teaching, and a sense of accomplishment help to rejuvenate new teachers.

Through their experiences in the first half of the year, beginning teachers gain new coping strategies and skills to prevent, reduce, or manage many problems they are likely to encounter during the second half of the year. Many feel a great sense of relief that they have made it through the first half of the year. During this phase, new teachers focus on curriculum development, long-term planning, and teaching strategies.

Reflection Phase

The reflection phase, beginning in May, is a particularly invigorating time for first-year teachers. Reflecting back over the year, they highlight events that were successful and those that were not. They think about the various changes that they plan to make the following year in management, curriculum, and teaching strategies. The end is almost in sight, and they have almost made it; but more importantly, a vision emerges as to what their second year will look like, which brings them to a new phase of anticipation.

It is critical that we assist new teachers and ease the transition from student teachers to full-time professionals. Recognizing the phases new teachers go through gives us a framework within which we can begin to design support programs to make the first year of teaching a more positive experience for our new colleagues. — Ellen Moir, New Teacher Center, University of California, Santa Cruz

No one can give you better advice than yourself. — Cicero

You aren’t thinking about it right now, but sometime in your future you’re going to miss a day of school.

This is the IDEAL time to begin preparing for that event because the questions you have now are the same questions a substitute teacher might have. Later, with a routine established, you may forget to think about such details.

Label a file folder or notebook “Substitute,” and keep it in a place anyone would logically look.

Here are some suggestions to include for your substitute:

E6 is the major practice for Leadership:

When you collaborate and the team works WITH you, then you will all be working toward the common goal. When you are all excited about where you are going, then you have created leadership.